The journey began when a group of researchers in 2015 and 2016 conducted a study to evaluate how feasible it was for community agents to visit the homes of pregnant women and newborns using cell phones to collect health information. They conducted this research in 13 communities in the Parinari district in Loreto and found that there was very good reception from the communities and that the agents were very enthusiastic about using the technology. Later, in 2017, the researchers lived in the communities to observe the cultural practices around pregnancy, childbirth, and newborn care, identifying positive practices around health and practices that could affect the health of mothers and babies.

Once this information was available, a group of researchers ventured into three districts: Nauta, Parinari and Saquena, between November 2018 and January 2019. They carried out a household census in 79 rural communities spread across 350 kilometers of river extension, gathering data from 1,027 mothers and their newborn babies. None of these communities had drinking water, electricity or drainage.

To understand how newborns are cared for in the Peruvian Amazon, nine key indicators of essential newborn care were used: three on thermal care, which included immediate drying of the baby, skin-to-skin contact of mother and baby, and delay of bath, at least for 24 hours; three on umbilical cord care, which included correct clamping or tying of the cord, clean cutting with a sterile instrument, and non-application of harmful substances to the cord; finally, three on breast milk feeding, which contemplated the consumption of colostrum, immediate start of breastfeeding, and exclusive breastfeeding for the first three days. Well, what was the situation in these remote communities?

Essential newborn care (ECNC) in remote communities in the Peruvian Amazon was found to leave much to be desired. Whether births at home or in medical facilities, they faced serious challenges. 65% of babies were born at home and of them, 93% without the help of trained personnel. There was a lack of basic infrastructure, for example, no post had electricity or drinking water, there were no trained or supervised staff, and lack of access to emergency obstetric care were very common.

One of the most surprising findings was the common belief that colostrum, the first milk, was harmful to babies. In reality, colostrum is vital for the baby's health. However, this belief persisted and negatively affected early and exclusive breastfeeding.

Another mystery was the practice of bathing the newborn. The WHO recommendations are to delay bathing the newborn for at least the first 24 hours, to maintain the protective layer with which they are born on their skin and prevent infections; However, bathing babies early and inappropriately was common practice. Although, inexplicably, in health centers it was more common than in home births to bathe babies too early; At home many mothers did it too.

Care to maintain an adequate temperature for the baby after birth and hygiene of the umbilical cord were insufficient both at home and in medical centers. Immediate skin-to-skin contact was rarely practiced and, furthermore, the lack of information meant that, at home, after cutting the cord, mothers used traditional substances such as ashes or oils to heal it. This and other practices increased the risk of infections. Additionally, limited access to postnatal care worsened the situation.

This research trip revealed that newborn care in the Peruvian Amazon was in urgent need of improvement. Identifying the gaps in essential newborn care practices allowed us to design a specific intervention to improve the care of babies in these communities.

The Mamás del Río project emerged in response to this need. A multidisciplinary team of health and social science professionals joined forces with key local actors: Community Health Workers (CHWs), who supported by traditional midwives and health personnel implemented a unique and effective approach to promote maternal health -children in these rural communities.

The CHWs are men and women members of the community and are elected by their neighbors. Thanks to their dedication, they became the backbone of the project, providing vital support and education in the community. Traditional midwives, guardians of ancestral knowledge, create a unique bond with mothers and their babies, and through the project, they were trained to ensure clean births.

Mamas del Río's journey began with training and mobilizing these key local actors, as well as raising community awareness. The results began to be evident: more mothers began to go to health centers to give birth, and newborn care practices improved significantly.

In 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic presented an unexpected challenge. Despite the restrictions and risks, Mamás del Río continued to operate, adapting to the new reality. The CHWs became a beacon of information about this virus that reached their communities and were vital support in a time of uncertainty. During the pandemic, health centers closed, residents could no longer travel through the rivers, however, the agents were there, in their communities, ensuring their health.

How effective was the project? This was measured by conducting annual follow-up studies for 3 years, through censuses in the same 79 rural communities in the districts of Nauta, Parinari and Saquena, through a survey on the essential care that the babies who were born had. Then, the results of the first census were compared with those of the census of year 2 and with those of year 3 to see if the changes were maintained over time.

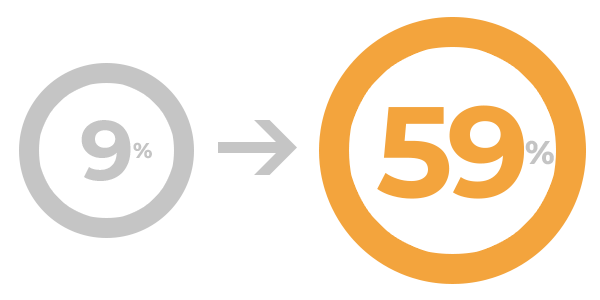

Increased skin-to-skin contact from 9 to 59%

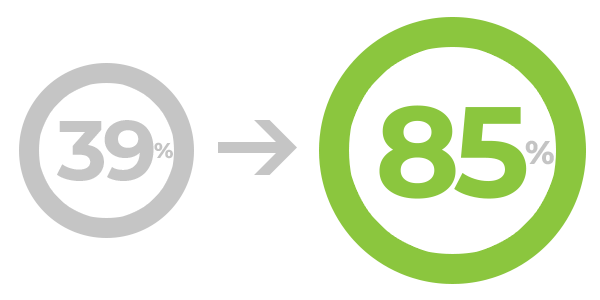

Increase in colostrum intake from 39% to 85%

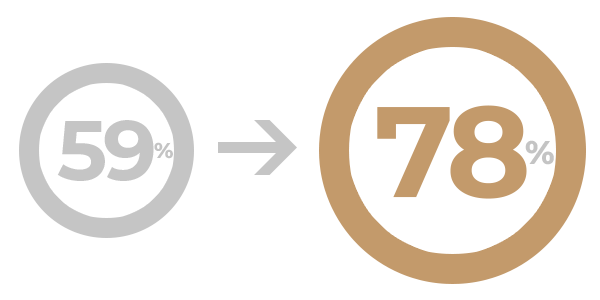

Umbilical cord care from 59 to 78%

Increased cord clamping with a sterile instrument from 78 to 93%

These follow-up studies revealed that newborn care practices greatly improved in home births, even taking into account the pandemic. The care practices that have increased the most are skin-to-skin contact, colostrum feeding, and hygienic care of the umbilical cord; but cord cutting and tying, delaying bathing, and exclusive breastfeeding also improved, and almost all of these practices are maintained over time!

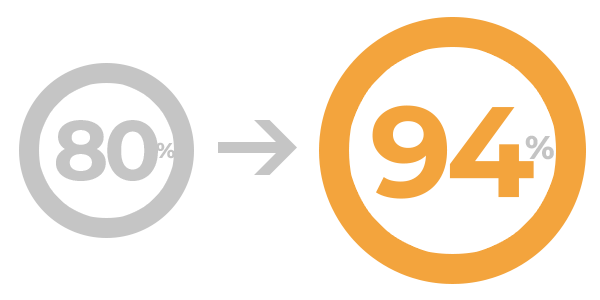

Delayed bathing of the baby: from 80 to 94%

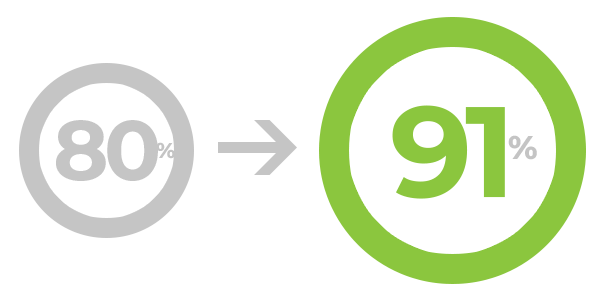

Increased clean cord cutting from 80 to 91%

Exclusive breastfeeding (1st 3 days) from 87 to 97%

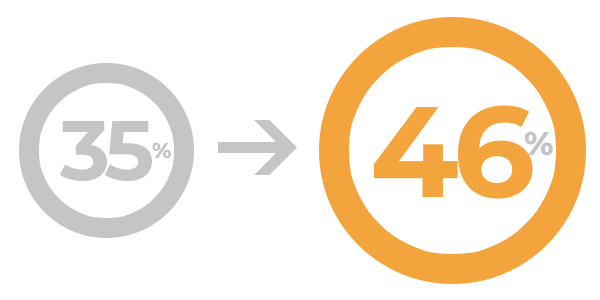

Increase in institutional births from 35 to 46%

The jungle moms have adopted safer and healthier practices, thanks to the tireless efforts of the CHWs, the midwives and the entire team behind Mamas del Río.

Article based in: "Home birth preference, childbirth, and newborn care practices in rural Peruvian Amazon" by Irene Del Mastro ,Paul Tejada-Llacsa, Stefan Reinders, Raquel Pérez, Yliana Solís, Isaac Alva & Magaly M. Blas; “Prevalence of essential newborn care in home and facility births in the Peruvian Amazon: analysis of census data from programme evaluation in three remote districts of the Loreto region” by Stefan Reinders, Magaly M. Blas, Melissa Neuman, Luis Huicho, & Carine Ronsmans; “Effect of the Mamás del Río programme on essential newborn care: a three-year before-and-after outcome evaluation of a community-based, maternal and neonatal health intervention in the Peruvian Amazon” by Magaly M. Blas, Stefan Reinders, Angela Alva, Melissa Neuman, Isabelle Lange, Luis Huicho & Carine Ronsmans; "Indigenous communities’ responses to the COVID-19 pandemic and consequences for maternal and neonatal health in remote Peruvian Amazon: a qualitative study based on routine programme supervision" by Reinders S., Alva A., Huicho L. & Blas M y "Study protocol: Evaluation of the Mamás del Río programme - a community-based, maternal and neonatal health intervention in Rural Amazonian Peru" by Reinders, Stefan; Blas, Magaly; Lange, Isabelle & Ronsmans, Carine.

©2024. Made with (❤︎) in Yachayninchik